|

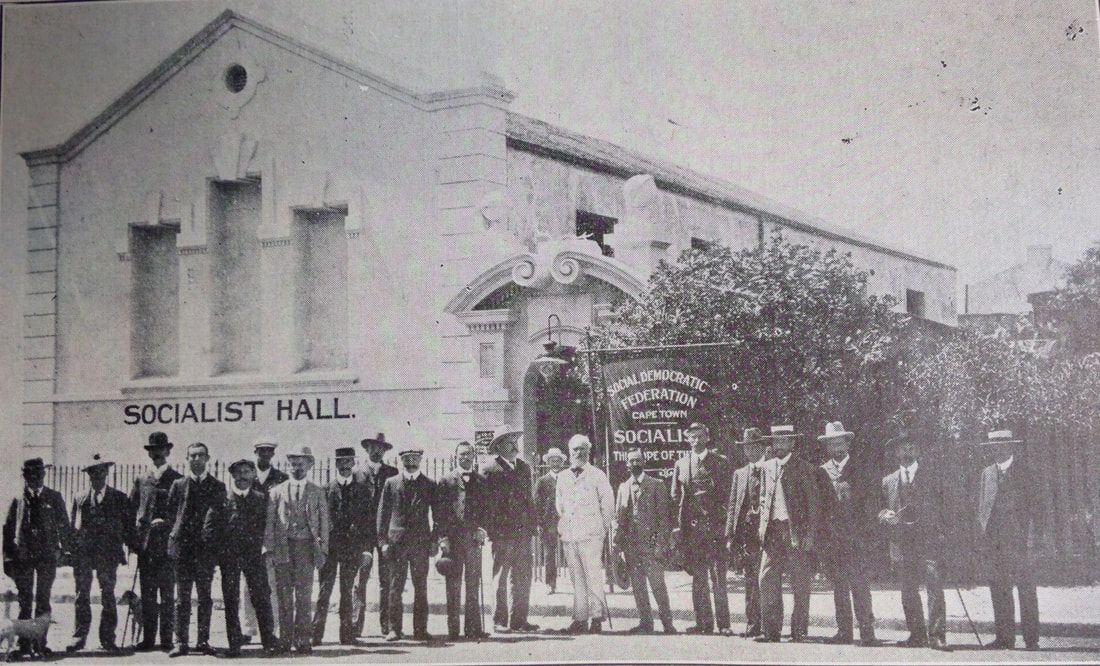

I have been in South Africa this week. Keir Hardie’s visit to India is reasonably well known, but he also stopped off in South Africa on his way home. You might have thought that the Boers would have welcomed him given he championed their cause during the Boer War. Unlike the Fabians, who supported the war, he saw it as a capitalists’ war. He admittedly had a rather romantic view of the Boer way of life, but he was proved right about the economic damage and the impact of militarism. However, while Hardie opposed imperialism, he also had a distinct class position that included race. He argued that the fundamental problems of Indian workers or black African miners were the same as the poor of Lanarkshire, Ayrshire or South Wales. They both suffered appalling living conditions, while the landowners and the bosses exploited them. He suggested that trade unions open themselves to blacks and share farmland. He championed the democratic rights of the majority and supported tribal lands, operating under their laws. Not a policy that was going to be popular in racist South Africa. Of course, Keir Hardie was never one to duck an unpopular cause! His meetings in Durban, Johannesburg and Ladysmith were all physically attacked. He narrowly escaped with his life from the Johannesburg venue. As Keir Hardie put it: “It will scarcely be credited by those not on the spot, but this produced as much sensation as though I had proposed to cut the throat of every white man in South Africa. The capitalist Press simply howled with rage – there were, of course, exceptions – and at Ladysmith a mob, led by a local lawyer, wrecked the windows of the hotel in which I was staying.” I visited Ladysmith, but sadly I suspect the hotel he spoke at is no more in a modern main street - although the town hall and the siege museum are from that period. Jonathan Hyslop puts Hardie’s position in context and explains the challenges it created for Labour supporters in South Africa. “Labourites in the white settlement colonies wanted to defend Hardie, as a representative figure of British labour, but were embarrassed by the fact that Hardie’s position on India went against the grain of White Labourist ideology. In southern Africa, local leaders of British labour did opt to defend Hardie. But they did so not only at the risk of alienating their members, but also at the price of being forced into direct confrontations with anti-Hardie groupings.” He also explains the basis for Hardie’s position and, to contemporary ears, the language he sometimes used: “He was a man of his time, seeking democratization of the Empire rather than its end, and his sympathy with the oppressed could coexist with constructs derived from contemporary racial ideology.” He ended his tour in Cape Town. Here he was better received as some Cape unions had opened their membership. There was an election, and The Labour Party was concerned that he might damage their campaign. However, The Social Democratic Federation organised a series of well supported and undisrupted meetings. Active hostility to Hardie in South Africa came mainly from middle- and upper-class British immigrants. British shopkeepers, members of volunteer colonial regiments, and supporters of pro-capitalist political groups. Many Afrikaners remembered his support during the Boer War. British working-class political activists were generally unsympathetic to the grievances of the Indians. Remember, this was where Gandhi cut his political teeth organising coal miner strikes and campaigning against punitive taxes on indentured workers. However, their allegiance to the British trade union tradition and their admiration for the Labour Party in the United Kingdom meant that they had great personal respect for Hardie. Dave Watson Secretary Keir Hardie Society Picture from Martin Plaut

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorThis is the Blog of the Keir Hardie Society. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed