Keir Hardie Speeches in the House of Commons

In this section we provide links to some of Keir Hardie's speeches made while he was an MP. in the House of Commons. Highlighting some key contributions.

Child Labour

In a parliamentary debate in February 2015, Keir Hardie challenged the use of child labour in agricultural districts. At the time every child between the ages of five and fourteen were nominally entitled public education. However:

"There always has been a certain strife in many agricultural districts between those who desire the children to be allowed to remain at school until they are fourteen and those who, especially in the agricultural industry, want the cheap labour of the children for their farms. It now looks as if the latter were becoming more powerful and were obtaining the approval of the Government. That is a serious situation."

He highlighted cases in Dorsetshire, Buckinghamshire. Devonshire, Gloucestershire, where in some instances boys of eleven years of age could be temporarily employed; Hampshire, where the chairman suggested that managers should be told not to prosecute for non-attendance if the parents desired boys of twelve years of age to leave school for farm work. It was also happening in manufacturing districts "in spite of the protestations of the trade unions that adult labour is available, and that the work to be done was too heavy for boys."

"That is the actual position that the bylaws issued to protect our children are being practically swept out of existence, as I hope to show before I finish, not because of any special necessity for child labour, but very largely as a means of perpetuating the uneducated sweated labour in our agricultural districts."

He argued that the war was being used as an excuse by employers "in the hope that the relaxation of the education laws will be perpetual, and that their cheap labour will be continued."

He pointed out that child labour was less prevalent in the north of England and Scotland because wages were almost double that in southern counties. He quoted The President of the Board of Education said:

"There is one curious fact in connection with this subject, and it is this, that where wages are lowest there has been the greatest tendency to lake children from school; where the conditions have been best, where the wages are highest, there is no demand on the part of the fanners to try and secure the cheap labour or the free labour of the boys on their farms."

His solution was to fix a statutory wage through wages boards and:

"Then, if we are to permanently solve this problem, there must be a fresh land policy. This country cannot afford to allow its land to be sacrificed and its labourers to be degraded in order to perpetuate an old-time system of private ownership, and before the agricultural problem can be solved some form of common local ownership and co-operation amongst the producers will require to be adopted."

The full debate can be read here.

Child Labour remains an issue today across the world. The International Labour Organization (ILO) launched the World Day Against Child Labour in 2002 to focus attention on the global extent of child labour and the action and efforts needed to eliminate it. Each year on 12 June, the World Day brings together governments, employers and workers organizations, civil society, as well as millions of people from around the world to highlight the plight of child labourers and what can be done to help them.

"There always has been a certain strife in many agricultural districts between those who desire the children to be allowed to remain at school until they are fourteen and those who, especially in the agricultural industry, want the cheap labour of the children for their farms. It now looks as if the latter were becoming more powerful and were obtaining the approval of the Government. That is a serious situation."

He highlighted cases in Dorsetshire, Buckinghamshire. Devonshire, Gloucestershire, where in some instances boys of eleven years of age could be temporarily employed; Hampshire, where the chairman suggested that managers should be told not to prosecute for non-attendance if the parents desired boys of twelve years of age to leave school for farm work. It was also happening in manufacturing districts "in spite of the protestations of the trade unions that adult labour is available, and that the work to be done was too heavy for boys."

"That is the actual position that the bylaws issued to protect our children are being practically swept out of existence, as I hope to show before I finish, not because of any special necessity for child labour, but very largely as a means of perpetuating the uneducated sweated labour in our agricultural districts."

He argued that the war was being used as an excuse by employers "in the hope that the relaxation of the education laws will be perpetual, and that their cheap labour will be continued."

He pointed out that child labour was less prevalent in the north of England and Scotland because wages were almost double that in southern counties. He quoted The President of the Board of Education said:

"There is one curious fact in connection with this subject, and it is this, that where wages are lowest there has been the greatest tendency to lake children from school; where the conditions have been best, where the wages are highest, there is no demand on the part of the fanners to try and secure the cheap labour or the free labour of the boys on their farms."

His solution was to fix a statutory wage through wages boards and:

"Then, if we are to permanently solve this problem, there must be a fresh land policy. This country cannot afford to allow its land to be sacrificed and its labourers to be degraded in order to perpetuate an old-time system of private ownership, and before the agricultural problem can be solved some form of common local ownership and co-operation amongst the producers will require to be adopted."

The full debate can be read here.

Child Labour remains an issue today across the world. The International Labour Organization (ILO) launched the World Day Against Child Labour in 2002 to focus attention on the global extent of child labour and the action and efforts needed to eliminate it. Each year on 12 June, the World Day brings together governments, employers and workers organizations, civil society, as well as millions of people from around the world to highlight the plight of child labourers and what can be done to help them.

Government involvement in industrial disputes - August 1911

There are some interesting parallels in the UK government's handling of the current industrial disputes with events in 1911: the one-sided approach, anti-trade union legislation and the use of troops.

The national railway strike of 1911 was the first nationwide strike of railway workers in Britain. It arose from longstanding disputes between workers and railway companies over the activities of the so-called 'conciliation boards', which had been set up to negotiate between workers and rail companies. The strike lasted only two days, but the show of strength forced the Liberal Government to set up a royal commission to examine the workings of the 1907 Conciliation Board.

The Liberal government were keen to ensure that the railways would not be shut down. Prime Minister Asquith told the rail companies that police and troops would be deployed to help keep the trains running. Troops were deployed in London and 32 other towns in England and Wales. The Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, suspended the Army Regulation, which required local authorities to request troops before they were sent.

These issues were debated in the House of Commons on Tuesday, 22 August 1911. Several MPs raised with Winston Churchill, then Home Secretary, why troops were being deployed, even when the local authority had not asked for them. This was the case in Manchester at the time.

Phillip Snowden MP asked why troops had been sent to Blackburn, "there had been no disturbance nor any indications whatever of the likelihood of disturbance; that the sending of the military was strongly resented by the civil authorities and the public, and was regarded as a provocative act tending to a breach of the peace.”

Churchill responded, "in the present situation the military authorities have been charged with general duties for protecting the property of the railways and for securing law and order in the maintenance of traffic.”

George Lansbury MP followed up: “Is it the ordinary law that the military officer commanding in the Metropolis can give an order to a squad of soldiers to invade the premises of the local borough council without their wish or desire? If that is so, why did the soldiers go away when they were ordered to go away?”

Ramsay MacDonald MP highlighted the government's one-sided approach, and Churchill in particular: “The bulletins which he issued, particularly the bulletin of Saturday, which gave great offence and very much hampered us in our negotiations, ought never to have been issued by a Government Department at all. The statements with which it opened were inaccurate, the expressions of opinion in the middle were not sensible, and the effect at the end was simply to make the men more inclined to go on fighting than to induce them to come to any settlement.”

This sounds all too familiar in today's disputes!

MacDonald continued: “The second point I want to raise is with regard to the reckless employment of force…… If the right hon. Gentleman wanted riots in Leicester, he just did exactly the thing that would produce them. There is one thing we will not do. We will not allow the ordinary civil operations of strikers, of men on strike, to be hampered and interfered with by a needless display of force, simply standing by and watching things done….. Organised labour in the country will not allow it, and, what is more, I think every person who has got the least idea of what civil liberty is will support us."

Keir Hardie also intervened in the debate saying: “The men voluntarily, cheerfully, and joyously resigned their services and came out on strike. If that is held to justify the employment of 58,000 soldiers, I leave the right hon. Gentleman whatever satisfaction it gives him…. (the government) have violated the law, have overridden the law, and suppressed civil government in this country without the consent or sanction of Parliament, and substituted military rule for it. These are the charges we make…. Talk about revolution! The law of England has been broken in the interests of the railway companies of this country…. instead of the government bringing pressure to bear upon the directors to settle the matter, they used all the forces of the Crown to intimidate the men.”

“Practically the Government said to the directors, ‘If a strike takes place, you get in your blackleg labour, carry on your restricted service, refuse to recognise the men's unions, and we will turn out every soldier in the country to assist you in your efforts to beat the men and keep wages low.’ There are no two opinions about it."

And referencing the two men shot dead by troops in Llanelli, he said: “The men who have been shot down have been murdered by the Government in the interests of the capitalist system.”

You can read the whole debate at:

https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1911-08-22/debates/097f19b8-9e68-4c47-a6e8-cda0a14eaa60/LabourDisputes

The national railway strike of 1911 was the first nationwide strike of railway workers in Britain. It arose from longstanding disputes between workers and railway companies over the activities of the so-called 'conciliation boards', which had been set up to negotiate between workers and rail companies. The strike lasted only two days, but the show of strength forced the Liberal Government to set up a royal commission to examine the workings of the 1907 Conciliation Board.

The Liberal government were keen to ensure that the railways would not be shut down. Prime Minister Asquith told the rail companies that police and troops would be deployed to help keep the trains running. Troops were deployed in London and 32 other towns in England and Wales. The Home Secretary, Winston Churchill, suspended the Army Regulation, which required local authorities to request troops before they were sent.

These issues were debated in the House of Commons on Tuesday, 22 August 1911. Several MPs raised with Winston Churchill, then Home Secretary, why troops were being deployed, even when the local authority had not asked for them. This was the case in Manchester at the time.

Phillip Snowden MP asked why troops had been sent to Blackburn, "there had been no disturbance nor any indications whatever of the likelihood of disturbance; that the sending of the military was strongly resented by the civil authorities and the public, and was regarded as a provocative act tending to a breach of the peace.”

Churchill responded, "in the present situation the military authorities have been charged with general duties for protecting the property of the railways and for securing law and order in the maintenance of traffic.”

George Lansbury MP followed up: “Is it the ordinary law that the military officer commanding in the Metropolis can give an order to a squad of soldiers to invade the premises of the local borough council without their wish or desire? If that is so, why did the soldiers go away when they were ordered to go away?”

Ramsay MacDonald MP highlighted the government's one-sided approach, and Churchill in particular: “The bulletins which he issued, particularly the bulletin of Saturday, which gave great offence and very much hampered us in our negotiations, ought never to have been issued by a Government Department at all. The statements with which it opened were inaccurate, the expressions of opinion in the middle were not sensible, and the effect at the end was simply to make the men more inclined to go on fighting than to induce them to come to any settlement.”

This sounds all too familiar in today's disputes!

MacDonald continued: “The second point I want to raise is with regard to the reckless employment of force…… If the right hon. Gentleman wanted riots in Leicester, he just did exactly the thing that would produce them. There is one thing we will not do. We will not allow the ordinary civil operations of strikers, of men on strike, to be hampered and interfered with by a needless display of force, simply standing by and watching things done….. Organised labour in the country will not allow it, and, what is more, I think every person who has got the least idea of what civil liberty is will support us."

Keir Hardie also intervened in the debate saying: “The men voluntarily, cheerfully, and joyously resigned their services and came out on strike. If that is held to justify the employment of 58,000 soldiers, I leave the right hon. Gentleman whatever satisfaction it gives him…. (the government) have violated the law, have overridden the law, and suppressed civil government in this country without the consent or sanction of Parliament, and substituted military rule for it. These are the charges we make…. Talk about revolution! The law of England has been broken in the interests of the railway companies of this country…. instead of the government bringing pressure to bear upon the directors to settle the matter, they used all the forces of the Crown to intimidate the men.”

“Practically the Government said to the directors, ‘If a strike takes place, you get in your blackleg labour, carry on your restricted service, refuse to recognise the men's unions, and we will turn out every soldier in the country to assist you in your efforts to beat the men and keep wages low.’ There are no two opinions about it."

And referencing the two men shot dead by troops in Llanelli, he said: “The men who have been shot down have been murdered by the Government in the interests of the capitalist system.”

You can read the whole debate at:

https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1911-08-22/debates/097f19b8-9e68-4c47-a6e8-cda0a14eaa60/LabourDisputes

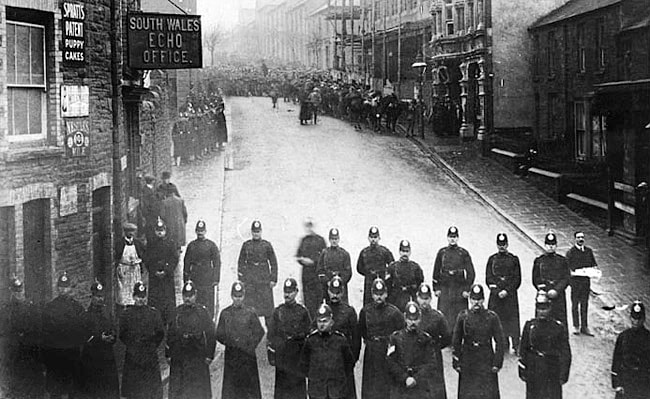

South Wales Coal Strike 1910-11

The South Wales Coal Strike started in September 1910 after the Naval Colliery Company locked out miners. The strike was an attempt by miners and their families to improve wages and living conditions in severely deprived parts of South Wales, where wages had been kept deliberately low for many years by a cartel of mine owners.

A series of violent confrontations between the striking coal miners and police took place at various locations in and around the Rhondda mines, which became known as the Rhondda or Tonypandy riots. Winston Churchill was the Home Secretary in the Liberal Government and he authorised the deployment of troops and the Metropolitan Police to the area. This was seen by those in Wales as an overreaction and led to a popular historical myth that troops fired on the miners. In fact, it was the Metropolitan Police who overreacted and and attacked local residents causing significant injuries.

Keir Hardie and other MPs called for a public inquiry into the behaviour of the police. This was debated in Parliament on 7 February 1911 (starting at Column 214). They read out several statements from local residents testifying to police violence, although Hardie was also critical about the conditions of police deployment. He said: "I think the Home Office must bear a very large share of the responsibility. When men are brought a very long distance in the midst of winter; when they are turned adrift amongst the Welsh hills without proper provision being made for housing, for feeding, even for clothing; when they are kept on duty for intolerably long hours, it is not to be wondered at that they get irritable and commit acts which, in their cooler moments, they probably regret."

There had been attempts to get recompense through the courts but as Hardie put it, "if a man gets his windows smashed by a riotous crowd or a policeman's truncheon, he can obtain compensation from the authorities, but if a man gets his head smashed he has no claim against anyone. Surely that is an anomalous state of things which should be inquired into with a view to being remedied. Property is no doubt very valuable, but it is no more valuable than life and limb."

Churchill's response was that he acted in a balanced way, arguing that the Tories had criticised him for not acting more strongly. As is the case today, the Tories could always be relied to support the employers. Hardie's case for an inquiry was summed up when he said: "Do not let us have an honest law-abiding, self-respecting class of workmen any longer held up to the stigma of having been riotous when we who know the men and know the place are aware that had the matter been left in the hands of the local police, not one single disturbance of a serious kind would ever have occurred. We ask for an inquiry in the first place as to whether unnecessary violence was used by the police, and if so what action ought to be taken to safeguard the public in the future; and, secondly, what is the law as to compensation for innocent persons injured."

A series of violent confrontations between the striking coal miners and police took place at various locations in and around the Rhondda mines, which became known as the Rhondda or Tonypandy riots. Winston Churchill was the Home Secretary in the Liberal Government and he authorised the deployment of troops and the Metropolitan Police to the area. This was seen by those in Wales as an overreaction and led to a popular historical myth that troops fired on the miners. In fact, it was the Metropolitan Police who overreacted and and attacked local residents causing significant injuries.

Keir Hardie and other MPs called for a public inquiry into the behaviour of the police. This was debated in Parliament on 7 February 1911 (starting at Column 214). They read out several statements from local residents testifying to police violence, although Hardie was also critical about the conditions of police deployment. He said: "I think the Home Office must bear a very large share of the responsibility. When men are brought a very long distance in the midst of winter; when they are turned adrift amongst the Welsh hills without proper provision being made for housing, for feeding, even for clothing; when they are kept on duty for intolerably long hours, it is not to be wondered at that they get irritable and commit acts which, in their cooler moments, they probably regret."

There had been attempts to get recompense through the courts but as Hardie put it, "if a man gets his windows smashed by a riotous crowd or a policeman's truncheon, he can obtain compensation from the authorities, but if a man gets his head smashed he has no claim against anyone. Surely that is an anomalous state of things which should be inquired into with a view to being remedied. Property is no doubt very valuable, but it is no more valuable than life and limb."

Churchill's response was that he acted in a balanced way, arguing that the Tories had criticised him for not acting more strongly. As is the case today, the Tories could always be relied to support the employers. Hardie's case for an inquiry was summed up when he said: "Do not let us have an honest law-abiding, self-respecting class of workmen any longer held up to the stigma of having been riotous when we who know the men and know the place are aware that had the matter been left in the hands of the local police, not one single disturbance of a serious kind would ever have occurred. We ask for an inquiry in the first place as to whether unnecessary violence was used by the police, and if so what action ought to be taken to safeguard the public in the future; and, secondly, what is the law as to compensation for innocent persons injured."

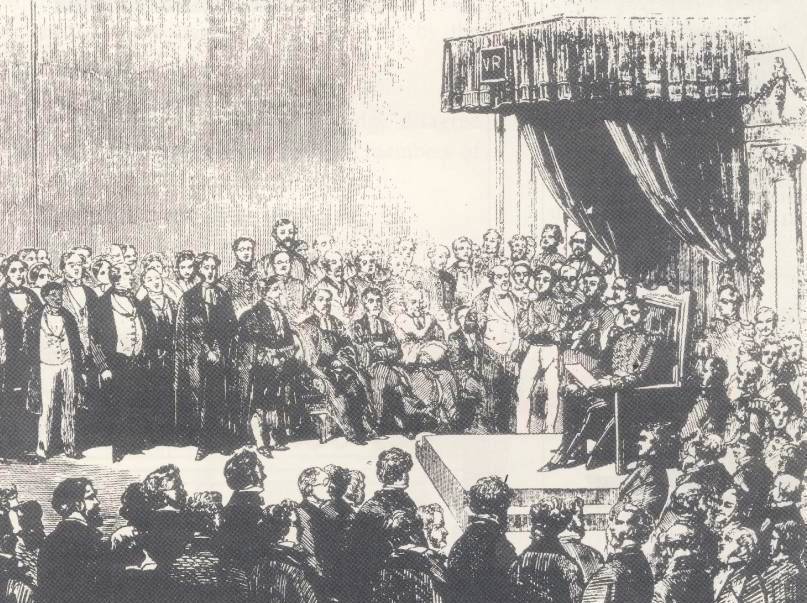

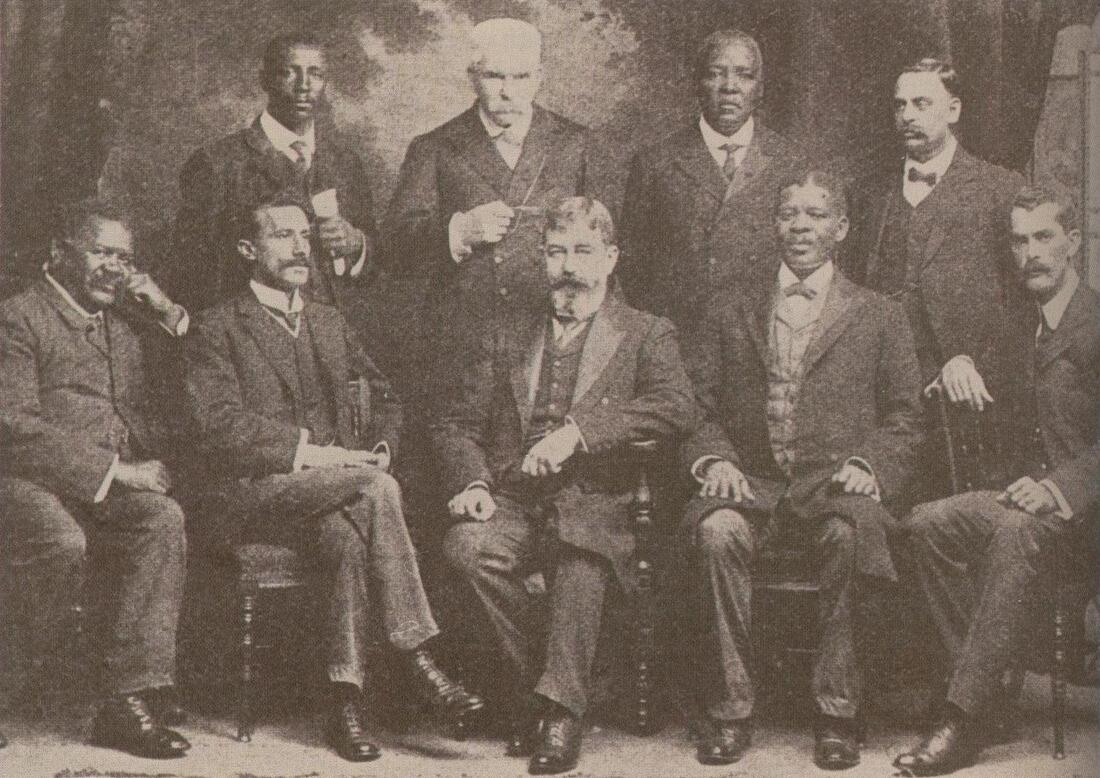

South Africa Bill

|

The South Africa Act 1909 created the Union of South Africa from the British colonies of the Cape of Good Hope, Natal, Orange River Colony, and Transvaal. The Cape Colony had long adhered to a system of non-racial franchise. However, according to the Act, Parliament was given the power to change the Cape's voting requirements by a two-thirds vote. Over the following years, legislation was passed by Parliament to slowly erode this colour-blind voters roll. Overall the Act did little to protect black Africans during the time period in which the South Africa Act was the constitution of South Africa, and ultimately enabled the establishing of fifty years of apartheid and racial discrimination.

This issue was recognised in the Commons debate (Starts at Column 951. Keir Hardie speech at 988). Keir Hardie addressed it directly when he said: "the point is that, for the first time we are asked to write over the portals of the British Empire: "Abandon hope all ye who enter here." So far as colour is concerned, this Bill lays it down that no native or person of other than European descent can ever hope to aspire to membership in the Parliament of South Africa, and if a native or a person of colour cannot hope to aspire to membership in that Parliament, to rob them of the franchise is a very short and very small step. I hope, therefore, that if only for the sake of the traditions of our dealings with natives in the past, this Bill—before it leaves the House of Commons—will be so amended as to make it a real unifying Bill in South Africa. At present it is a Bill to unify the white races, to disfranchise the coloured races, and not to promote union between the races in South Africa, but rather to still further embitter the relationships." |

|