Keir Hardie and Home Rule

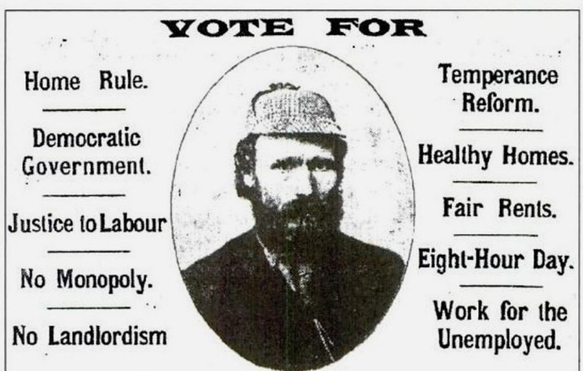

Keir Hardie’s 1888 Lanark By-Election poster has Home Rule as one of his commitments to the electorate. In 1889 he wrote: "I believe the people of Scotland desire a Parliament of their own and it will be for them to send to the House of Commons a body of men pledged to obtain it."

As the Secretary of the Keir Hardie Society, I have to regularly explain that Hardie's support for Home Rule is not the same as independence. He came from the Liberal tradition of Home Rule, primarily focused on Ireland during his lifetime. A tradition recently highlighted in Ben Thomson’s book, ‘Scottish Home Rule’. He defines Home Rule as “a bilateral arrangement between one area within a nation state and the rest of that nation state. This is distinct from federalism, which represents an equal relationship between all constituent parts of a country”. This makes Home Rule a more practical option for the asymmetric UK, although he argues that it could provide a template for the UK to move towards federalism. The difference between Home Rule and devolution is that people in Scotland would know control over domestic matters is decided solely by them, and that Westminster and its Prime Minister cannot unilaterally overrule this.

To understand Keir Hardie's support for Home Rule, we need to go back before devolution. Scotland maintained separate institutions following the Treaty of Union in 1707 - in particular (Article 19) a separate legal system. This helped keep a national identity and arguably a different approach to politics and government. Nineteenth-Century Scotland was not the centralised state it would become before devolution. The town councils were powerful bodies, and Scottish local supervisory boards administered welfare, leading, as Gordon Brown states, “The Scottish public would see the boards and the local councils, rather than the distant Whitehall and Westminster, as responsible for the routine government of Scotland."[i].

In the 1880’s it was the Irish question that drove the Home Rule debate. While Hardie did have support from the Scottish Home Rule Association, it had little influence in Mid Lanark. Hardie was more concerned to show his support for Home Rule in Ireland, given the large numbers of Irish residents in the constituency. The Irish National League provided significant support to his campaign through the registration of Irish voters.

There is a conventional, if contested, view that Irish Home Rule held back the development of Labour politics during a period when sectarianism was never far from the surface. William Kenefick[ii] reminds us that many Lowland middle-class Scots were resentful that the Irish had made the issue of Irish Home Rule a factor in Scottish politics. For many in Protestant West of Scotland, with its strong links to Ulster, ’Home Rule’ meant ‘Rome Rule’. Sectarianism wasn't, of course, a one-way street. Knox states[iii] that Catholic Irish miners in Lanarkshire considered ‘Protestantism…. more obnoxious than low wages”. This would have been a real challenge for Hardie because sectarianism affected the coalfields more than any other industry.

Keir Hardie’s position on Irish Home Rule must have been less than obvious to some after the formation of the Scottish Labour Party in 1888. Emrys Hughes, in his biography of Hardie[iv] tells the story of a meeting in the Camlachie constituency of Glasgow that had a large Irish population. Local ‘roughs’ invaded the meeting because “people did not know Keir Hardie’s attitude towards Irish Home Rule”. Cunninghame-Graham, chairing the meeting, had to brandish a fake pistol to maintain order. However, they were both carried out of the hall with acclaim after Hardie spoke strongly in favour of Home Rule for Ireland.

Kenefick also points to the links between land reform and Home Rule in the 1880s. This linked back to an older, radical anti-landlord tradition that went back to the days of Chartism. Land reformers seeking broader support extended the aims of the Highland ‘land war’ movement to the Lowlands, and in 1884, the Scottish Land Restoration League was founded. It was backed by Hardie and affiliated with the Scottish Labour Party in 1888. The more explicitly socialist Scottish Land and Labour League also affiliated in 1888. These movements popularised the idea of Home Rule and had political success. The Crofters Party secured the election of five MPs in the 1884 election, and this encouraged those who argued in favour of supporting independent candidates against official Liberalism.

Gladstone was committed to treating all nations the same way and promised that a Scottish Home Rule Bill would follow his Irish Home Rule Bill. However, Gladstone's Home Rule programme was certainly not independence, as the supremacy of the Imperial Parliament would be maintained. This led to the creation of the Scottish Home Rule Association in 1886 and the conversion of Scottish Liberals to Home Rule in 1888. It also led to a split within the Liberals, with the Whigs who opposed Home Rule joining the Conservatives. Hardie welcomed this split as he assumed this would result in a more progressive Liberal Party.

Hardie was also no bystander in the Home Rule movement. He was among the vice-presidents of the Scottish Home Rule Association, and Ramsey MacDonald was the Secretary of the London branch. The first Scottish Home Rule motion was introduced in the House of Commons in 1889, regularly followed by motions and first readings of bills up to the First World War. The 1913 Bill went as far as a second reading.

It might be argued that the formation of the STUC as a separate organisation to the TUC reflected a degree of nationalism within organised labour of which Hardie was rooted. However, others[v] point to the parochialism of trade unions during this period with strong district and regional structures. Centralisation only gained significant ground with new unionism in the run-up to the First World War. The STUC’s formation, as their evidence to the Kilbrandon Commission put it, “reflected the uneasiness in Scottish trade union circles about the ‘remoteness’ of London”. However, the decision of the TUC to debar Trades Councils from participation in Congress decisions was probably more important, given the greater role they played in the Scottish trade union movement.

The STUC unanimously adopted the principle of Home Rule at the 1914 Congress. A tradition that the STUC continues to this day. It is also clear from speeches by trade union leaders of the time that Home Rule was very different from separatism. They saw the need for a body to focus on local issues while still joining with the British and Irish congresses to, as Robert Smillie put it, “the improvement of the condition of workers of the country as a whole”.[vi]

This is also the period of Hardie’s conversion from Liberalism to socialism, driven by the Lanarkshire miners strike and the failure of the Liberal Party to support the eight-hour clause in the 1887 Mines Bill. The founding programme of the Scottish Labour Party in May 1888 included Home Rule for each separate nationality in the British Empire with an Imperial Parliament for imperial affairs. This commitment to Home Rule was seen as part of the early Labour leaders radical and Liberal heritage.

As Hardie's efforts focused on forming a British Independent Labour Party (ILP), the greater engagement of trade unions put Home Rule lower on the agenda. The 1901 programme of the Scottish Workers Representation Committee (including the ILP) had no specific mention of Home Rule for Scotland. Keating and Bleiman[vii]conclude that Home Rule remained part of the policy of Labour in Scotland up to 1914, but it was limited to an expression of general support. The priorities were the more important social needs of the working class and the greater integration of the labour movement on a British basis.

Hardie's publication[viii] ‘From Serfdom to Socialism’ was published in 1907. He sets out his basic principles of socialism with chapters on municipal socialism, the state, Christianity, workers and women. However, Home Rule does not feature. In fairness, the work focuses on principles rather than organisation.

Home Rule does not appear to be a significant part of Hardie’s ideology as a politician. In July 1892, Hardie had been elected as the MP for West Ham South in London, although he did not entirely ignore Home Rule even in that election. He agreed with Gladstone’s Newcastle Programme and stressed the Home Rule elements, although he would later call it a “miscellaneous compendium of odds and ends”[ix]. He also lost the support of many Irish voters because he said his support for Home Rule had been with a ‘bad conscience’, although that was apparently because of a proposal to set up a House of Lords. Two local priests said he made Ireland the 'tail of a socialist programme’.

Hardie could certainly see the dangers of nationalism to the working class. When in Dublin and Belfast pleading the cause of solidarity during the transport workers strike, and later during the Ulster Protestant rebellion against Home Rule. He viewed these developments as the political right protecting landed interests against the growing strength of working people.

Hardie certainly supported colonial emancipation. He led the British delegation at the 1904 Congress of the International, at which the Indians sent a delegate for the first time. He rattled the Raj during his 1907 visit to India when he said, “The sooner the people of India controlled their own affairs the better”. He kept the pressure up when he returned to the UK with a pamphlet called “India: Impressions and Suggestions’. However, there is no suggestion in any of these campaigns that he regarded Scotland or Wales as colonies. Caroline Benn, in her conclusion, puts it this way;

“How the common wealth was administered, and by what forms of democratic accountability control was exercised, were details he was often content to leave to others, though he always favoured strong local oversight and parliaments for Scotland, Wales and Ireland.”

Kenneth Morgan, in his biography[x] of Hardie argues that while there are gaps in his version of socialism, his focus was sociological, not economic and “never hedged around by rigid dogma”. While Morgan has little to say about Hardie and Home Rule, he does point to his pamphlet, The Common Good (1910), in which Hardie wrote enthusiastically about municipal reform and the ownership of transport, utilities and municipal trading. Although he envisaged that these would lead to public ownership at the national level as well. It can therefore be argued that Hardie was not a natural centraliser and explicitly opposed it - the local tradition remained important to him.

Bob Holman interpreted Hardie’s call for Home Rule as a call for independence. During the 2014 independence referendum, he argued in The Herald[xi] that Hardie’s Home Rule was the same as independence. He based this claim on Hardie's call for more working-class MPs and railing against the elitism of Westminster. He also said that Hardie would have welcomed gender balance, something he campaigned vigorously on. Indeed, he probably would have, but that is mainly due to the Scottish Labour Party's 50:50 policy, not the Parliament. Finally, of course, Hardie would have attacked privatisation and inequality, but these are political decisions, not a consequence of constitutional reform.

To claim that Hardie was a nationalist is a challenging conclusion to draw from the historical evidence. His life and work had the obvious UK and broader international solidarity context. My first job as a full-time union official was in South Wales. I remember attending a meeting in Merthyr Tydfil Town Hall where Hardie's wonderful bust was inspirational to a young idealistic union official. More recently, Newham Council in London has published an excellent booklet commemorating Hardie's time as the MP for West Ham. It is hard to imagine a Scottish nationalist politician standing for an English or Welsh constituency.

I would argue that the evidence above shows that Home Rule for Hardie reflected the Liberal tradition he was part of. It certainly survived his conversion to socialism and remained part of the programme of the wider Labour movement during this period - albeit with a much lower priority. The Liberal leadership of this period was, as Tom Devine argues[xii], unenthusiastic about Home Rule and their proposals imply something closer to limited administrative reform than real self-government. The Liberal tradition was closer to what we would describe as devolution today, and not even the more radical part of that movement, than independence.

The Scottish Home Rule Association was not campaigning for independence. Its vice-chair John Romans said, “No Scotsman whose opinion is worth repeating, entertains for a moment, an approximation to repeal the union”.[xiii]This is because Home Rule was viewed as part of a distinct Scottish national identity within the wider union. Even the 1913 Government of Scotland Bill, the most advanced of the Home Rule bills, fell somewhat short of what we would call Devo-Max or Full Fiscal Autonomy today.

The Labour movement and Hardie had bigger priorities in this period. Challenging capital, trade union immunities and improving social conditions were the key issues. In addition, they sought common ground with workers across the UK and political reform at Westminster, rather than an independent Scotland. This culminated in the STUC and the Labour Party abandoning support for Home Rule by 1932.

While we should be wary of applying 21st Century values to a 19th Century politician, there are some things we can be reasonably clear about. Keir Hardie was a socialist, not a nationalist. His and the early Labour Party’s support for Home Rule was part of the Liberal tradition that was closer to what we would recognise as devolution today. Its importance declined as Hardie, and the early pioneers of the Labour Movement focused on other priorities.

The lesson we should take from the life and work of Keir Hardie is that he took the message of socialism to hundreds of thousands of ordinary people across the UK. He changed the way a generation thought about what was possible, an alternative vision of what today we would call social justice.

Dave Watson

Secretary

www.keirhardiesociety.org

July 2021

You can download a PDF version of this article here

[i] Brown, Gordon, My Scotland, Our Britain, Simon & Shuster 2014.

[ii] Kenefick, William, Red Scotland! Edinburgh University Press 2007

[iii] Knox, William, Industrial Nation, Edinburgh University Press, 1999

[iv] Hughes, Emrys, Keir Hardie, Lincolns-Prager, London

[v] Keating & Bleiman, Labour and Scottish Nationalism, Macmillan 1979.

[vi] Ibid p44

[vii] Ibid p58

[viii] Hardie, J.Keir, From Serfdom to Socialism, George Allen, 1907

[ix] Benn, Caroline, Keir Hardie, Richard Cohen Books 1997

[x] Morgan, Kenneth, Keir Hardie: Radical and Socialist, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1975

[xi] Holman, Bob, Why Ed Miliband should learn the lessons of Keir Hardie, Herald 12 September 2014 http://www.heraldscotland.com/comment/columnists/agenda.25275697

[xii] Devine, Tom, The Scottish Nation 1700-2000 Allen lane 1999

[xiii] Quoted in Mills and others, Myths, Realties, Radical Future, Red paper Collective 2015

To understand Keir Hardie's support for Home Rule, we need to go back before devolution. Scotland maintained separate institutions following the Treaty of Union in 1707 - in particular (Article 19) a separate legal system. This helped keep a national identity and arguably a different approach to politics and government. Nineteenth-Century Scotland was not the centralised state it would become before devolution. The town councils were powerful bodies, and Scottish local supervisory boards administered welfare, leading, as Gordon Brown states, “The Scottish public would see the boards and the local councils, rather than the distant Whitehall and Westminster, as responsible for the routine government of Scotland."[i].

In the 1880’s it was the Irish question that drove the Home Rule debate. While Hardie did have support from the Scottish Home Rule Association, it had little influence in Mid Lanark. Hardie was more concerned to show his support for Home Rule in Ireland, given the large numbers of Irish residents in the constituency. The Irish National League provided significant support to his campaign through the registration of Irish voters.

There is a conventional, if contested, view that Irish Home Rule held back the development of Labour politics during a period when sectarianism was never far from the surface. William Kenefick[ii] reminds us that many Lowland middle-class Scots were resentful that the Irish had made the issue of Irish Home Rule a factor in Scottish politics. For many in Protestant West of Scotland, with its strong links to Ulster, ’Home Rule’ meant ‘Rome Rule’. Sectarianism wasn't, of course, a one-way street. Knox states[iii] that Catholic Irish miners in Lanarkshire considered ‘Protestantism…. more obnoxious than low wages”. This would have been a real challenge for Hardie because sectarianism affected the coalfields more than any other industry.

Keir Hardie’s position on Irish Home Rule must have been less than obvious to some after the formation of the Scottish Labour Party in 1888. Emrys Hughes, in his biography of Hardie[iv] tells the story of a meeting in the Camlachie constituency of Glasgow that had a large Irish population. Local ‘roughs’ invaded the meeting because “people did not know Keir Hardie’s attitude towards Irish Home Rule”. Cunninghame-Graham, chairing the meeting, had to brandish a fake pistol to maintain order. However, they were both carried out of the hall with acclaim after Hardie spoke strongly in favour of Home Rule for Ireland.

Kenefick also points to the links between land reform and Home Rule in the 1880s. This linked back to an older, radical anti-landlord tradition that went back to the days of Chartism. Land reformers seeking broader support extended the aims of the Highland ‘land war’ movement to the Lowlands, and in 1884, the Scottish Land Restoration League was founded. It was backed by Hardie and affiliated with the Scottish Labour Party in 1888. The more explicitly socialist Scottish Land and Labour League also affiliated in 1888. These movements popularised the idea of Home Rule and had political success. The Crofters Party secured the election of five MPs in the 1884 election, and this encouraged those who argued in favour of supporting independent candidates against official Liberalism.

Gladstone was committed to treating all nations the same way and promised that a Scottish Home Rule Bill would follow his Irish Home Rule Bill. However, Gladstone's Home Rule programme was certainly not independence, as the supremacy of the Imperial Parliament would be maintained. This led to the creation of the Scottish Home Rule Association in 1886 and the conversion of Scottish Liberals to Home Rule in 1888. It also led to a split within the Liberals, with the Whigs who opposed Home Rule joining the Conservatives. Hardie welcomed this split as he assumed this would result in a more progressive Liberal Party.

Hardie was also no bystander in the Home Rule movement. He was among the vice-presidents of the Scottish Home Rule Association, and Ramsey MacDonald was the Secretary of the London branch. The first Scottish Home Rule motion was introduced in the House of Commons in 1889, regularly followed by motions and first readings of bills up to the First World War. The 1913 Bill went as far as a second reading.

It might be argued that the formation of the STUC as a separate organisation to the TUC reflected a degree of nationalism within organised labour of which Hardie was rooted. However, others[v] point to the parochialism of trade unions during this period with strong district and regional structures. Centralisation only gained significant ground with new unionism in the run-up to the First World War. The STUC’s formation, as their evidence to the Kilbrandon Commission put it, “reflected the uneasiness in Scottish trade union circles about the ‘remoteness’ of London”. However, the decision of the TUC to debar Trades Councils from participation in Congress decisions was probably more important, given the greater role they played in the Scottish trade union movement.

The STUC unanimously adopted the principle of Home Rule at the 1914 Congress. A tradition that the STUC continues to this day. It is also clear from speeches by trade union leaders of the time that Home Rule was very different from separatism. They saw the need for a body to focus on local issues while still joining with the British and Irish congresses to, as Robert Smillie put it, “the improvement of the condition of workers of the country as a whole”.[vi]

This is also the period of Hardie’s conversion from Liberalism to socialism, driven by the Lanarkshire miners strike and the failure of the Liberal Party to support the eight-hour clause in the 1887 Mines Bill. The founding programme of the Scottish Labour Party in May 1888 included Home Rule for each separate nationality in the British Empire with an Imperial Parliament for imperial affairs. This commitment to Home Rule was seen as part of the early Labour leaders radical and Liberal heritage.

As Hardie's efforts focused on forming a British Independent Labour Party (ILP), the greater engagement of trade unions put Home Rule lower on the agenda. The 1901 programme of the Scottish Workers Representation Committee (including the ILP) had no specific mention of Home Rule for Scotland. Keating and Bleiman[vii]conclude that Home Rule remained part of the policy of Labour in Scotland up to 1914, but it was limited to an expression of general support. The priorities were the more important social needs of the working class and the greater integration of the labour movement on a British basis.

Hardie's publication[viii] ‘From Serfdom to Socialism’ was published in 1907. He sets out his basic principles of socialism with chapters on municipal socialism, the state, Christianity, workers and women. However, Home Rule does not feature. In fairness, the work focuses on principles rather than organisation.

Home Rule does not appear to be a significant part of Hardie’s ideology as a politician. In July 1892, Hardie had been elected as the MP for West Ham South in London, although he did not entirely ignore Home Rule even in that election. He agreed with Gladstone’s Newcastle Programme and stressed the Home Rule elements, although he would later call it a “miscellaneous compendium of odds and ends”[ix]. He also lost the support of many Irish voters because he said his support for Home Rule had been with a ‘bad conscience’, although that was apparently because of a proposal to set up a House of Lords. Two local priests said he made Ireland the 'tail of a socialist programme’.

Hardie could certainly see the dangers of nationalism to the working class. When in Dublin and Belfast pleading the cause of solidarity during the transport workers strike, and later during the Ulster Protestant rebellion against Home Rule. He viewed these developments as the political right protecting landed interests against the growing strength of working people.

Hardie certainly supported colonial emancipation. He led the British delegation at the 1904 Congress of the International, at which the Indians sent a delegate for the first time. He rattled the Raj during his 1907 visit to India when he said, “The sooner the people of India controlled their own affairs the better”. He kept the pressure up when he returned to the UK with a pamphlet called “India: Impressions and Suggestions’. However, there is no suggestion in any of these campaigns that he regarded Scotland or Wales as colonies. Caroline Benn, in her conclusion, puts it this way;

“How the common wealth was administered, and by what forms of democratic accountability control was exercised, were details he was often content to leave to others, though he always favoured strong local oversight and parliaments for Scotland, Wales and Ireland.”

Kenneth Morgan, in his biography[x] of Hardie argues that while there are gaps in his version of socialism, his focus was sociological, not economic and “never hedged around by rigid dogma”. While Morgan has little to say about Hardie and Home Rule, he does point to his pamphlet, The Common Good (1910), in which Hardie wrote enthusiastically about municipal reform and the ownership of transport, utilities and municipal trading. Although he envisaged that these would lead to public ownership at the national level as well. It can therefore be argued that Hardie was not a natural centraliser and explicitly opposed it - the local tradition remained important to him.

Bob Holman interpreted Hardie’s call for Home Rule as a call for independence. During the 2014 independence referendum, he argued in The Herald[xi] that Hardie’s Home Rule was the same as independence. He based this claim on Hardie's call for more working-class MPs and railing against the elitism of Westminster. He also said that Hardie would have welcomed gender balance, something he campaigned vigorously on. Indeed, he probably would have, but that is mainly due to the Scottish Labour Party's 50:50 policy, not the Parliament. Finally, of course, Hardie would have attacked privatisation and inequality, but these are political decisions, not a consequence of constitutional reform.

To claim that Hardie was a nationalist is a challenging conclusion to draw from the historical evidence. His life and work had the obvious UK and broader international solidarity context. My first job as a full-time union official was in South Wales. I remember attending a meeting in Merthyr Tydfil Town Hall where Hardie's wonderful bust was inspirational to a young idealistic union official. More recently, Newham Council in London has published an excellent booklet commemorating Hardie's time as the MP for West Ham. It is hard to imagine a Scottish nationalist politician standing for an English or Welsh constituency.

I would argue that the evidence above shows that Home Rule for Hardie reflected the Liberal tradition he was part of. It certainly survived his conversion to socialism and remained part of the programme of the wider Labour movement during this period - albeit with a much lower priority. The Liberal leadership of this period was, as Tom Devine argues[xii], unenthusiastic about Home Rule and their proposals imply something closer to limited administrative reform than real self-government. The Liberal tradition was closer to what we would describe as devolution today, and not even the more radical part of that movement, than independence.

The Scottish Home Rule Association was not campaigning for independence. Its vice-chair John Romans said, “No Scotsman whose opinion is worth repeating, entertains for a moment, an approximation to repeal the union”.[xiii]This is because Home Rule was viewed as part of a distinct Scottish national identity within the wider union. Even the 1913 Government of Scotland Bill, the most advanced of the Home Rule bills, fell somewhat short of what we would call Devo-Max or Full Fiscal Autonomy today.

The Labour movement and Hardie had bigger priorities in this period. Challenging capital, trade union immunities and improving social conditions were the key issues. In addition, they sought common ground with workers across the UK and political reform at Westminster, rather than an independent Scotland. This culminated in the STUC and the Labour Party abandoning support for Home Rule by 1932.

While we should be wary of applying 21st Century values to a 19th Century politician, there are some things we can be reasonably clear about. Keir Hardie was a socialist, not a nationalist. His and the early Labour Party’s support for Home Rule was part of the Liberal tradition that was closer to what we would recognise as devolution today. Its importance declined as Hardie, and the early pioneers of the Labour Movement focused on other priorities.

The lesson we should take from the life and work of Keir Hardie is that he took the message of socialism to hundreds of thousands of ordinary people across the UK. He changed the way a generation thought about what was possible, an alternative vision of what today we would call social justice.

Dave Watson

Secretary

www.keirhardiesociety.org

July 2021

You can download a PDF version of this article here

[i] Brown, Gordon, My Scotland, Our Britain, Simon & Shuster 2014.

[ii] Kenefick, William, Red Scotland! Edinburgh University Press 2007

[iii] Knox, William, Industrial Nation, Edinburgh University Press, 1999

[iv] Hughes, Emrys, Keir Hardie, Lincolns-Prager, London

[v] Keating & Bleiman, Labour and Scottish Nationalism, Macmillan 1979.

[vi] Ibid p44

[vii] Ibid p58

[viii] Hardie, J.Keir, From Serfdom to Socialism, George Allen, 1907

[ix] Benn, Caroline, Keir Hardie, Richard Cohen Books 1997

[x] Morgan, Kenneth, Keir Hardie: Radical and Socialist, Weidenfeld & Nicholson 1975

[xi] Holman, Bob, Why Ed Miliband should learn the lessons of Keir Hardie, Herald 12 September 2014 http://www.heraldscotland.com/comment/columnists/agenda.25275697

[xii] Devine, Tom, The Scottish Nation 1700-2000 Allen lane 1999

[xiii] Quoted in Mills and others, Myths, Realties, Radical Future, Red paper Collective 2015