|

Keir Hardie and the Boer War

Hardie was not in Parliament at the start of the Boer War, and his views were expressed in the Labour Leader. In an article printed in L’Humanitie Nouvelle and reprinted in the Labour Leader, he wrote: “We are told it is to spread freedom and extend the rights of the common people, but it is really about getting a market for goods, investors, an outlay for capital, and companies' cheaper labour.” But he then took a view of the Boers that he would reverse later in life, especially after he left the Labour Leadership and campaigned in support of the excluded minorities in South Africa. This campaign put his life in danger from the then Boer-dominated government. In 1899, he wrote: “As socialists, our sympathies are bound to be with the Boers. They have a republican form of government, and they produce for use rather than exploitation for profit.” However, his opposition to the war and his pacifism were instrumental in his selection for Merthyr and his return to Parliament. In 1901, he opposed a payment of £4000 to the Commander in Chief of the British forces in the war, gaining the support of 58 MPs, mainly from Ireland. Jim O'Neil

0 Comments

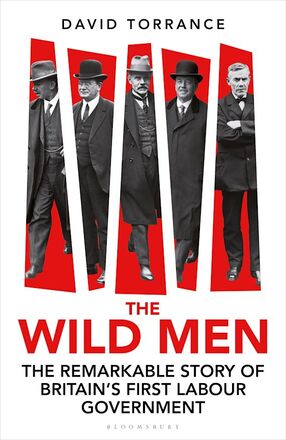

This year is the centenary of the very first Labour Government in the UK, led by Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. David Torrance has written an excellent new history of that government in The Wild Men.www.bloomsbury.com/uk/wild-men-9781399411431/ We recently published an outline of the story of that government and posed some lessons from history for the Labour Party today. So, I won't repeat the basic facts. jan_24_election.pdf David's approach highlights what a major event this was to the British body politic. The King was more pragmatic than you might expect. When asked to reflect on the change of government, the King was said to have replied: ‘My grandfather would have hated it; my father could hardly have tolerated it; but I march with the times.’ Others were less pragmatic. It provoked hysterical predictions that the ‘forces of order’ would be paralysed, public finances shattered and Britain reduced to ‘an outlaw state’. There would be no protection, ran another alarmist headline, ‘for anyone who wears a clean collar’. The King was less pragmatic when it came to the prospect of the Soviet Union being officially recognised. The new Prime Minister argued that other European countries were preparing to do so and that, if UK did not, it would miss out on economic opportunities. The King's distaste was a bit rich given what we now know of the Royal Family's refusal to offer sanctuary to the Romanovs.

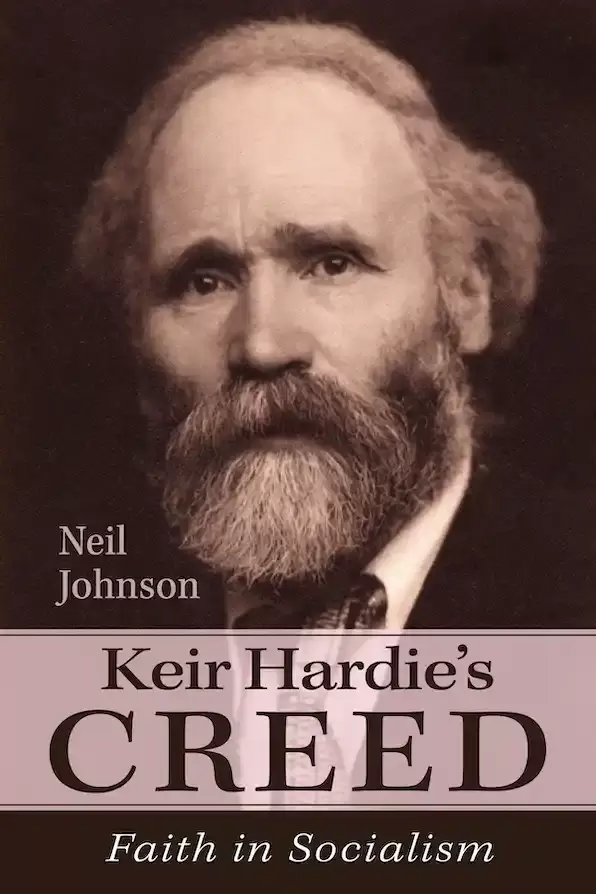

David's approach is to go through all the key members of the Cabinet to highlight the achievements and challenges the minority government faced. Strategically, MacDonald had a clear aim: to complete the political realignment which had begun during the war, ‘elbow the Liberals aside and make Labour the permanent alternative to the Conservatives in a new two-party system’. MacDonald was less sure footed when it came to the decisions which dogged his government and he took on too much himself. After four gruelling months he was undoubtedly worn out. Even the Archbishop of Canterbury and Asquith had noticed that the Prime Minister was suffering from neuritis; in March he was plagued by headaches and the after-effects of influenza, Some issues have not been resolved to this day. Arthur Henderson held the view that decisions of the Labour Party conference were binding, while the Prime Minister regarded them as little more than ‘soundings of party sentiment’ that could be ignored. One minister who stands out is John Wheatley. ‘He is an extreme socialist & comes from Glasgow,’ the King noted in his diary. ‘I had a very interesting conversation with him.’ The King asked searching questions about Wheatley’s childhood, in response to which the minister painted a vivid picture of the grinding hardship endured by his parents and their eight children, who had inhabited a miner’s cottage without drainage or running water. To this the King apparently listened in ‘friendly sympathy’ before asking rhetorically: ‘Is it possible that my people live in such awful conditions?’ Then, as the King bade the minister farewell, he reportedly added: ‘I tell you, Mr. Wheatley, that, if I had to live in conditions like that, I would be a revolutionary myself.’ As McLean put it, ‘The solid brick terraces which march across the inner suburbs of every British city, could not have been built without John Wheatley …They are the monument to the greatest of the Clydesiders.’ The Chancellor, Phillip Snowden was less radical. He cut taxation to the tune of £38 million for the forthcoming fiscal year but left income tax, surtax and death duties completely untouched, The Capital Levy proposed by the Chancellor and his colleagues during the general election, was jettisoned. When John Maynard Keynes suggested Snowden should have spent £100 million on construction engineering, Hugh Dalton remarked that it was ‘a little humiliating humiliating to find ourselves less bold than this Liberal economist.' Expectations of the first Labour Government by its supporters were high. However, As J. R. Clynes observed in his memoirs, Labour suffered because a number of its supporters ‘expected us to do everything in a few weeks’ – ‘unemployment would immediately vanish, poverty would cease, opportunity and wealth would be suddenly equalised’ – and, when it became clear they ‘could not perform miracles’, those supporters ‘bitterly’ abused the government. While important steps were made in foreign affairs, housing and education, little progress was made in tackling the scourge of unemployment - Keir Hardie would not have been impressed! The Prime Minister’s political hero had been Keir Hardie and Hardie had unequivocally supported Scottish Home Rule. This pledge, first made in 1888, endured as the Labour Party grew in Scotland and across Great Britain. However, in office MacDonald lost his enthusiasm for the project. Writing to ILP and Scottish Home Rule Association activists he said, 'I am afraid at the moment it is impossible for me with all the burdens of straightening out matters to go into the details about Scottish Home Rule.' He was not alone, outwith the Clydesiders, who kept the faith - Labour politicians had come to see Home Rule as potentially damaging to the unity and solidarity of the British working class. A minority government was always going to be time limited. The Campbell case was badly handled but didn't have to bring the government down. But MacDonald was exhausted 'carrying the burden both of a Prime Minister’s day-to-day business and a succession of gruelling diplomatic negotiations with the great powers of Europe’. The subsequent election was marked by the almost certainly forged Zinoviev Letter, although it probably did little more than scare middle-class Liberals to vote Tory. The Labour vote actually increased although they lost seats. The Liberals collapsed, bringing about MacDonald's strategic objective of a two-party state. Torrance concludes that 'many governments with substantial majorities and fuller parliamentary terms have delivered less.' he is also sympathetic to MacDonald, even his later treachery. The main charge against MacDonald has been that his absorption with foreign affairs led him to neglect the home front, and that includes Scotland. Attlee probably summed up the government's greatest achievement saying, 'The mere formation of a Labour Government and its existence for nine months registered a vital change in the political situation.' The ‘wild men’ so feared in late 1923 had shown they were competent men after all. Labour were fit to govern. This is a superbly researched study of the period - highly recommended. New Keir Hardie books are rare, so Neil Johnson's Keir Hardie’s Creed: Faith in Socialism is welcome. This slim and very readable book focuses on how Christianity influenced Keir Hardie's life. It is the first in-depth exploration of Hardie's religious socialism. The introduction sets the context and short biography of Hardie. He then discusses Christian socialism and how that label might or might not be applied to Hardie's views. The author distinguishes between Christian socialists and socialist Christians, with the latter discovering values in socialism that had been lost to the church. Hardie's perspectives on organised religion are well known, probably best set out in his pamphlet, Can a Man be a Christian on a Pound a Week, and these are reflected in the institutional attacks on him. He also said, 'The rich and comfortable classes had annexed Jesus and perverted his Gospel.’ Words that were not likely to endear him to the church hierarchy!

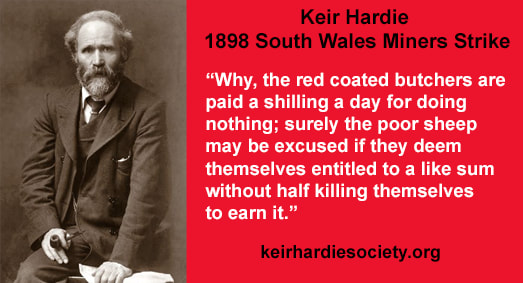

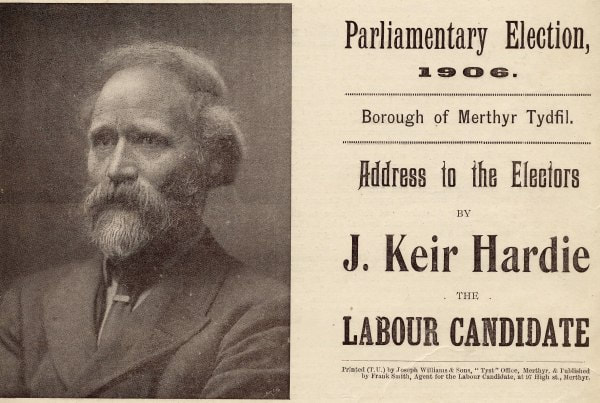

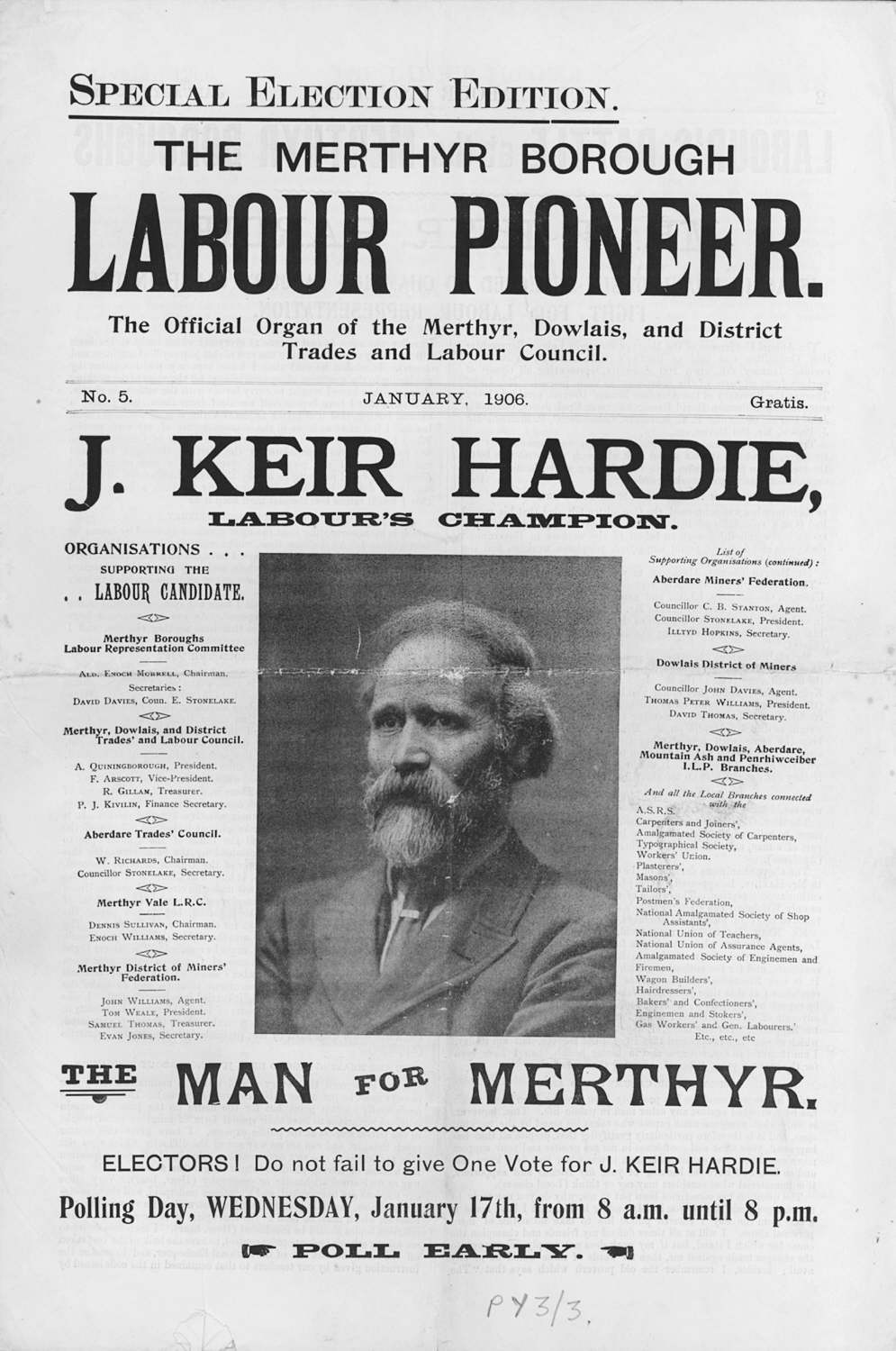

The author argues that Hardie's Christianity was Christ-centred – a very personal faith in the person of Jesus. Hardie often distinguished between the Christianity of Jesus and the 'Churchianity’ of contemporary Christians. In the Labour Leader in 1900, he said, 'Christ never once denounced the poor, weak erring sinner. He kept the invectives of His wrath for the clergy and religious folk of His day.' His faith was also practical. In answer to the question, 'Do the churches heed the poor?' Hardie replied, 'The Sermon on the Mount is the panacea, not creeds. Doing, not believing, the former only makes one a Christian.' As an agitator, he also fell within the prophetic tradition. This led him to reference the Jewish prophets as well as other religions, including Islam, the Baha'i Faith and Mandaeism. He regarded John the Baptist as a revolutionary leader and called on his spirit to purge the genteel assemblies of the organised church. Religion was not the only influence on Keir Hardie. His socialism was also built on the work of Robert Burns and Karl Marx. Thomas Carlyle was influential in his early years, although by 1909, he had discovered his failings. Hardie was always a 'big tent' socialist, adopting many historical and contemporary figures to the cause. He found a common thread stretching back to the Hebrew prophets, Jesus and the early church. The common theme was nonconformity. The author concludes that the theological foundation of the Evangelical Union gave Hardie a concept of God that emphasised the egalitarianism of grace personified in Jesus – the labourer and political agitator. The liberation struggle had been pursued by people inspired by their values and beliefs – labour history is religious history. This is a valuable addition to the body of work that examines not only Keir Hardie’s actions but also his beliefs. Well worth a read. The 1900 general election was held between 26 September and 24 October 1900, as voting then took place on different days in different constituencies. It is also called the Khaki Election because the ruling Conservatives, led by Lord Salisbury, hoped to capitalise on recent successes in the Boer War. However, the war was far from won and would grind on for another two years. This wouldn’t be the last time this ploy was used, with Lloyd George doing the same in 1918 and Margaret Thatcher in 1982 after the Falklands War. Keir Hardie was a Scot and had previously been the MP for West Ham South. He was also vehemently opposed to the Boer War, which might appear to be running against the jingoistic tide in the country at large. However, Hardie was no stranger to South Wales. In 1896, he had targeted South Wales with leaflets translated into Welsh and started a socialist society the following year. During the 1898 miners' strike in South Wales, Hardie had toured the coalfields, raising money for the miners through the Leader special strike fund. He even persuaded wealthy donors like Walter Crane, Thomas Lipton and George Cadbury to contribute. He was particularly critical of Lib-Lab miners’ MPs for failing to support the strike properly. The strike failed, but it did raise political consciousness. The miners started to meet politically and decided to put up Labour candidates against the Liberals who had let them down. The number of ILP branches in South Wales grew from 11 to 31. When the election was called, Hardie was reluctantly persuaded to stand in Preston (you could stand in two constituencies), a strong Tory seat with a garrison and a significant Catholic vote. The anti-war Cadbury’s (Hardie called them ‘the chocolate folks’) were prepared to fund his campaign only because there was no Liberal candidate there. Meanwhile, allies in South Wales wanted Hardie to stand in Merthyr Tydfil and worked out that they could fund the campaign through ILP and the newly formed Trades Councils. The Merthyr miners supported a conservative Lib-Lab Mining Federation Official called Brace for the seat. However, rank-and-file miners packed the meeting and won Hardie the nomination. Hardie benefited from a split between the two Liberal candidates. D.A. Thomas was a radical who opposed the war, while P. Morgan supported it. Morgan was a gold prospector who had rarely been seen in the constituency and was investing in foreign coal, a threat to Welsh mines. The prospective Tory candidate thought Merthyr was in Newcastle, then Cardiff, missing his nomination. While imperialism was strong, there was also a pacifist tradition. He also benefited from a working-class radicalism that could be traced back to the Merthyr riots in 1831, Chartism, and the post-Reform Act election of 1868. Hardie set out for Merthyr after losing at Preston, only spending around 11 hours campaigning, although he benefitted from the loan of the new-fangled motor car. Voting took place in Merthyr on 3 October, and to everyone's amazement, he squeezed into second place 1700 votes ahead of Morgan (Thomas, 8,598; Hardie, 5,645; and Morgan, 4,004). The South Wales Daily Post called it ‘the greatest possible surprise’ and ‘an astonishing result.’ The miners carried him back to his hotel on their shoulders. He was one of only two Labour Representation Committee members elected. Queen Victoria died before the new Parliament was due to convene in 1901. Hardie's first motion regretted that Queen Victoria had not seen fit to 'recommend the office of hereditary ruler be abolished.' After that was ruled out of order, he opposed the civil list expenditure for the new King because 'when taxes were being increased... when wages were going down', huge increases for the royal family were 'indefensible'. He also stuck to his anti-war position, saying: "I appeal for the independence of the Boers as a means of settlement, because we have no right to take their independence from these people. It is not that we cannot subdue the Boers, that is not my point of view. The words "Do unto others as ye would they should do unto you" apply to nations as they do to individuals, and a nation professing to be Christian should do its best to uphold so sacred a charge. Not only are we trying to do that which we have no right to do, but we are attempting the impossible. Our army may wear down the Boer resistance, but you cannot wear down the Boer independence." (Hansard, 26 February 1901, Line 1276) Despite these issues, Hardie's focus was, as ever, on poverty and industrial policy. Attacking the capitalists and landlords, as well as the established church. He identified himself with the leading progressive causes in Wales and supported Home Rule for Wales as he had for Scotland. The Red Dragon and the Red Flag was his watchword – radical socialism in a highly distinctive Merthyr form. The constituency became the base for building the labour movement. In April 1901, Hardie made is famous 'Case for Socialism' speech in Parliament. This has been reproduced in an excellent video by Royal Holloway University. Hardie successfully defended the seat in the 1906 and then the 1910 election. This was despite a virulent media campaign funded by the Anti-Socialist Coalition. They flooded the constituency with anti-Hardie material supported by the Merthyr Express and Western Mail. Leaflets described Hardie as a libertine, atheist and a wealthy man. He was so wealthy that he apparently owned a 'castle in Scotland'. The Liberals distributed 'an indecent picture of him... calculated to make people think him an advocate of free love.' Hardie said, 'No one can know what suffering a man has to endure by misrepresentation.' Hardie would not be the last Labour leader to face such a media campaign! On a personal note, my first full-time union job was in South Wales. As a very young official, one of my first meetings was in the old Merthyr Town Hall. At the top of the grand stairs inside the building was a bust of Keir Hardie welcoming me to the struggle. An inspiration I have never forgotten. Dave Watson A recent episode of Melvin Bragg's 'In Our Time' programme was on the Temperance Movement. It reminded me that when doing an after-dinner speech on Keir Hardie, I always point out that the great man would not have approved of the alcohol being consumed!

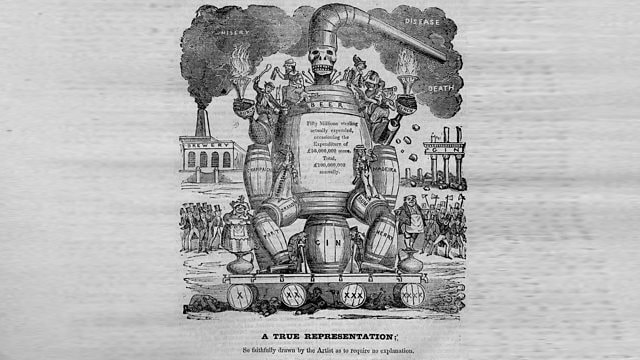

In Keir Hardie's time, drink flourished among the very poor and was probably a bigger problem than drugs are today. Hardie's stepfather could be abusive when drunk, and drink was a strong tradition in certain trades, including shipbuilding and mining. Keir Hardie and his mother believed that drink was a widespread social evil that had to be countered by social action. They saw hope in the temperance movement that had been strong in Scotland since the 1840s. Hardie took the pledge when he was seventeen. The movement was not just a puritanical and religious movement. It was strongly associated with radical liberalism and the early socialists. A tradition followed by other Scottish socialists, including John Maclean, Willie Gallagher and Tom Johnston. It was also a significant social movement with libraries and friendly societies. Temperance was arguably Hardie's first political cause. He campaigned for the strict enforcement of existing laws and legal prohibition. Hardie promoted his view in his column in the Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald. The Good Templar membership in Cumnock had quadrupled in the 1880s, and the local press put this down to Hardie's efforts. Many of his policy prescriptions may sound dated today, but they are not a long way from the solutions advocated by many to the drugs problem today. However, it was an uphill battle, as many Liberals regarded legislation on this issue as a challenge to their freedoms. Hardie's instincts sided with state control, a precursor of his later conversion to socialism. In parliament, he supported 'local option' proposals to shut down the local liquor trade, 'Those who can take a glass or let it alone,' he said, are 'under moral obligation for the sake of weaker brethren who cannot do so, to let it alone.' Labour conference voted for state control and for local option. As the 'In our Time' programme highlighted, the temperance movement was huge in the Nineteenth century and can be seen to this day with Temperance halls in many towns. Preston was at the forefront of the movement, a radical reputation that it continues to this day as a champion of the Community Wealth Building movement. So, when you raise a glass to Keir Hardie, remember he would not have approved, for a good reason! Parallels in history over a century later are fraught with difficulties. However, there are some parallels with the imperialist aims of modern Russia in their invasion of Ukraine and the financing of their interests through the UK financial system.

In Keir Hardie's day, Russia was the great dictatorship, the apogee of feudal cruelty and imperial oppression. British socialists worked closely with Russian exiles, including many Jews escaping persecutions. Hardie was particularly friendly with the nihilist Sergius Stepniak and the anarchist Prince Kropotkin, both exiles in London. He strongly supported allowing refugees into the country escaping persecution in eastern Europe during the debate over the Aliens Bill of 1905. This was when right-wing politicians were busy exploiting racial prejudice in the east end of London and other cities. The main business of the ILP Easter Conference in 1908 was to declare its opposition to the Russian government for its 'infamous tyranny' which 'condemned great numbers of our Russian comrades to imprisonment, torture, and death.’ If this sounds familiar to current events, it may well be because Vladimir Putin has a 19th-century imperialist view of Russia and a similar approach to dissidents. In arguably another analogous call, Hardie condemned an official visit to Russia by King Edward VII. Hardie protested in Parliament, accusing the King of going in order to render Russia safe for European capitalists to exploit. The root cause of the 1907 entente with Russia was the need to protect British investors in the Near East, as Russian troops invaded Persia. He accused the King of condoning Russian ‘atrocities’, referencing the shooting of political and industrial demonstrators. When the Tsar made a return visit, Hardie was one of the first to oppose the visit. In Parliament, he said the Tsar 'did not represent the people of Russia, and King Edward did not represent the people of Great Britain.’ The Tsar never left his ship at Cowes. Hardie is also well known for his opposition to war. He was present at the 1904 Congress of the International when the Russo-Japanese war broke out, which opposed that conflict, as Hardie had done earlier over the Boer War. A war he argued as being for the profits of the few, mainly Rhodes. He argued that the working class should not ‘bow to the yoke of imperialism.' Hardie, the pacifist, believed socialism was 'revolutionary' but 'that it can only be won by violent outbreak is in no sense true.’ He also opposed the First World War, and he despaired as German and French socialists supported their respective governments. The Labour Party initially declared against the war, but it also bent to the war fever of the initial war period. Even in his address to the anti-war meeting in Trafalgar Square on 2 August 1914, he had Russia in his sights, ‘We should not be in this position but for our alliance with Russia. Friends and comrades, this very square has rung with denunciations of Russian atrocities. Surely if there is one country under the sun which we ought to have no agreement with it is the foul government of anti-democratic Russia.’ Had he succeeded in uniting workers across Europe, millions of lives would have been saved. Dave Watson Secretary This week is the 200th anniversary of the Radical Rising or Radical War as it is also known. A less well-known part of Scotland’s working-class history, often overshadowed by events like the Peterloo Massacre, which took place the previous year. The radical movement in Scotland was influenced by the American and French revolutions as well as tracts like Thomas Paine’s ‘The Rights of Man’. Increasing literacy in Scotland, thanks to the education system, brought these ideas to a wider audience. Scotland had eight newspapers in 1782, and that had grown to twenty-seven by 1790. There was also a nationalist element brought about by disaffection with the Treaty of Union - exacerbated by measures including Scotland being described officially as ‘North Britain’ and the abolition of the office of Secretary of State for Scotland. The Burns song ‘A Parcel of Rogues in a Nation’ sums up this view. The uprisings in Ireland had a limited synergy in Scotland with envoys from the United Irishmen attending a convention in Edinburgh in 1793. The Scottish ‘Friends of the People’ planned an uprising, but its leaders Watt and Downie were arrested. Watt was executed, and Downie was transported. A new republican organisation was formed after this based around secret United Scotsmen societies. Plans for an uprising died away after the Government’s success in Ireland. While republican uprisings may have had limited support, there was a big growth in radicalism. The end of the Napoleonic wars brought economic depression. From 1760 to 1813 wages rose by 60% while the cost of living rose by 130%. Labourers were deprived of their smallholdings, and common land was enclosed. The profits from industrialisation went into the pockets of employers while the price of wheat trebled in less than 20 years. Radical organisation was based on weavers’ union societies based in most villages, until broken by the Government in 1812. After the employers refused to abide by a court decision on wage levels, 20,000 weavers went on strike. It was eventually broken in February 1813, having lasted nine weeks. By 1819 the radical movement had continued to grow along with the wider British movement. The Paisley Radical Committee was the strongest in the country with some 30,000 people attending a rally on Meikleriggs Muir on July 17 1819 – a month before Peterloo. After that military style drilling took place most evenings and the CinC of the army sought to strengthen security at Yeomanry depots. A Peterloo protest meeting on September 11 in Paisley, attracted 14-18,000 people from across Ayrshire, Renfrewshire and Glasgow. These were followed by riots and meetings across the central belt, and the military was called in to suppress them. The Government was convinced a large-scale uprising was planned by the 28-man Committee for Organising a Provisional Government, formed to coordinate the Radical Committees. They paid agents to infiltrate the movement, and most of the committee were arrested following a meeting in Glasgow on March 21 1820. These informers then turned agent-provocateurs by announcing that a rising was imminent and helped organise the collection of weapons. They also organised the printing and distribution of a proclamation on April 1. It called for a rising, "To show the world that we are not that lawless, sanguinary rabble which our oppressors would persuade the higher circles we are but a brave and generous people determined to be free”. The English references to Magna Carta probably point to it being written by a government spy. Some 60,000, mainly weavers, downed tools on April 3. A few badly organised risings were provoked by government agents including the march on the Carron Ironworks and in Strathaven. The aim was to flush out the radical leadership while large numbers of troops were billeted in the central belt. In Greenock, rioters freed prisoners from the local jail. Hundreds of radicals fled by ship to Canada to escape persecution, while 88 men were charged with treason. A number were acquitted, but James Wilson was hanged and beheaded in Glasgow on August 30, and a similar fate befell Andrew Hardie and John Baird in Stirling on September 8. Nineteen more were transported, although subsequently pardoned in 1835.

The 1820 Society seeks to publicise and commemorate the Scottish Radical Insurrection of 1820. It carries out its commemorative function by holding rallies at the three 1820 Monuments.

There was a debate in the Scottish Parliament on 5 September 2001 (motion S1M-2101) on the subject of 1820 and the education curriculum. It would be fair to say that politicians of all parties picked their own lessons from the uprisings in the debate, but it at least highlighted the event. The 1820 insurrection may not have been an immediate success, but it did reflect a much wider radical feeling in Scotland and Britain during the period. It also forms part of the radical tradition that did eventually lead to political reform. Albeit using different tactics. The family of Keir Hardie liked to speculate on their kinship to Andrew Hardie, something Keir Hardie did not discourage despite it being his adopted name. When asked about this, his daughter Nan said simply ‘my father …. had some queer notions.’ Further Reading: The Radical Rising: The Scottish Insurrection of 1820 by Peter Berresford Ellis and Seumas Mac a’Ghobhainn. Originally published in 1970, the 2016 paperback is in print. The authors arguably put something of a nationalist spin on events, but it is well researched and remains the best study of the insurrection. Most people will be familiar with the Great Famine or Great Hunger, a period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1849. Outside Ireland, it is often referred to as the Irish Potato Famine. Less well known is that the potato blight also affected many parts of Scotland during the same period, leading to protests and riots. These are documented in James Hunter’s new book, ‘Insurrection: Scotland’s Famine Winter’.

Some of the most violent riots took place in the North East of Scotland, Inverness and Caithness. The Western Isles were also badly hit by the famine and this led to a further stage of the land clearances and migration to North America. Absentee landlords, some of which invested their generous slave compensation payments in Highland and Aberdeenshire land, promoted migration.

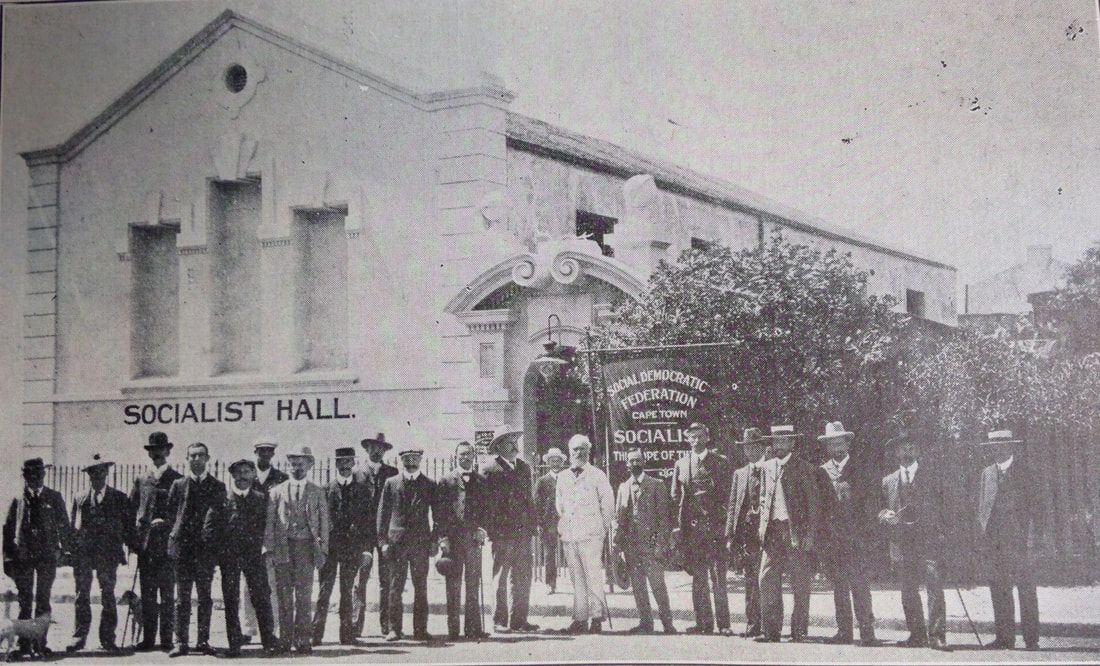

For example, John Gordon of Cluny sent nearly 1,700 people to Canada. ‘These parties,’ a senior immigration officer noted of people reaching Quebec from Gordon’s estate, ‘presented every appearance of poverty and . . . were without the means . . . of procuring a day’s subsistence for their helpless families on landing.’ The insurrections were eventually put down by the military, although this took some time as there were few soldiers stationed in Scotland. At the outset, only 240 in Aberdeen and 55 at Fort George. There were no railways in the north of Scotland at this time, and only one Royal Navy gunboat available to transport troops. Law and order was enforced by a handful of constables and specials enrolled from the ‘reliable’ middle classes. However, many of these were sympathetic to the rioters and were in any case overwhelmed by the numbers involved. The courts handed down punitive transportation sentences, in actions reminiscence of the Tolpuddle Martyrs case. As the Manchester Times noted “the men who supported the . . . exclusion are in high office and honour, and the poor young fellow who obstructed the exportation of a boatload of corn, when his neighbours had the horrors of starvation before their eyes, is sentenced to ten years transportation.” The famine also raised political consciousness. The Whig MP for Caithness, who was in the pocket of the local landowner, complained, “They are great readers and their local press is of the worst description, tending . . . to preach socialism and its accompanying doctrines.” The Chartists were also active in the areas affected. The authorities in Inverness made strenuous efforts in 1839 to deny venues for Chartist meetings organised by the Aberdeen Chartist, Alexander MacKenzie. He had similar problems in Macduff and Elgin. Hunter also notes the prevalence of shoemakers in radical activity, something which had been a feature of continental revolutionary activity. Some historians have argued that there was no organised activity behind the riots. However, Hunter points out that while riot and disturbance was endemic in these communities, theft was not. Many of the actions were also well organised, such as in Inverness in 1847 when roadblocks were established around the town. Although there is limited evidence of wider political goals other than the relief of famine. The authorities were forced to respond with food supplies and the sentences were reduced. Not welcomed by The Scotsman newspaper, which reverted to its long-standing conviction that crofters, said to be ‘men who love to live without without work’, needed to be ‘disabused’ of any notion that they might be deserving of help from outside. The later extension of the franchise brought radical Highland land reform (HLLRA) candidates into the 1885 election including Gavin Clarke as the MP for Caithness. As a student, he joined the International Working Men’s Association, regarded Karl Marx as a guiding light, and was for some time on good terms with our very own James Keir Hardie. As Hunter says in the concluding chapter, “Might there have been among the Bridge Street crowd, on the day when Gavin Clark became MP for Caithness, at least one or two people – in their fifties or sixties now – who were in that same street, on an equally snowy day in February 1847, when the Riot Act was read and a harbour-bound grain cart brought forcibly to a halt?” There is a lot of detail in this book about the impact of the famine on Scotland, and pretty harrowing it is. It also highlights the establishment attitudes of the day and some nascent political responses. In all, a very worthwhile contribution to our understanding of the period and the insurrection that the famine provoked. Dave Watson January 2020 Ps. The book is half price at Waterstones in Glasgow at present. I have been in South Africa this week. Keir Hardie’s visit to India is reasonably well known, but he also stopped off in South Africa on his way home. You might have thought that the Boers would have welcomed him given he championed their cause during the Boer War. Unlike the Fabians, who supported the war, he saw it as a capitalists’ war. He admittedly had a rather romantic view of the Boer way of life, but he was proved right about the economic damage and the impact of militarism. However, while Hardie opposed imperialism, he also had a distinct class position that included race. He argued that the fundamental problems of Indian workers or black African miners were the same as the poor of Lanarkshire, Ayrshire or South Wales. They both suffered appalling living conditions, while the landowners and the bosses exploited them. He suggested that trade unions open themselves to blacks and share farmland. He championed the democratic rights of the majority and supported tribal lands, operating under their laws. Not a policy that was going to be popular in racist South Africa. Of course, Keir Hardie was never one to duck an unpopular cause! His meetings in Durban, Johannesburg and Ladysmith were all physically attacked. He narrowly escaped with his life from the Johannesburg venue. As Keir Hardie put it: “It will scarcely be credited by those not on the spot, but this produced as much sensation as though I had proposed to cut the throat of every white man in South Africa. The capitalist Press simply howled with rage – there were, of course, exceptions – and at Ladysmith a mob, led by a local lawyer, wrecked the windows of the hotel in which I was staying.” I visited Ladysmith, but sadly I suspect the hotel he spoke at is no more in a modern main street - although the town hall and the siege museum are from that period. Jonathan Hyslop puts Hardie’s position in context and explains the challenges it created for Labour supporters in South Africa. “Labourites in the white settlement colonies wanted to defend Hardie, as a representative figure of British labour, but were embarrassed by the fact that Hardie’s position on India went against the grain of White Labourist ideology. In southern Africa, local leaders of British labour did opt to defend Hardie. But they did so not only at the risk of alienating their members, but also at the price of being forced into direct confrontations with anti-Hardie groupings.” He also explains the basis for Hardie’s position and, to contemporary ears, the language he sometimes used: “He was a man of his time, seeking democratization of the Empire rather than its end, and his sympathy with the oppressed could coexist with constructs derived from contemporary racial ideology.” He ended his tour in Cape Town. Here he was better received as some Cape unions had opened their membership. There was an election, and The Labour Party was concerned that he might damage their campaign. However, The Social Democratic Federation organised a series of well supported and undisrupted meetings. Active hostility to Hardie in South Africa came mainly from middle- and upper-class British immigrants. British shopkeepers, members of volunteer colonial regiments, and supporters of pro-capitalist political groups. Many Afrikaners remembered his support during the Boer War. British working-class political activists were generally unsympathetic to the grievances of the Indians. Remember, this was where Gandhi cut his political teeth organising coal miner strikes and campaigning against punitive taxes on indentured workers. However, their allegiance to the British trade union tradition and their admiration for the Labour Party in the United Kingdom meant that they had great personal respect for Hardie. Dave Watson Secretary Keir Hardie Society Picture from Martin Plaut

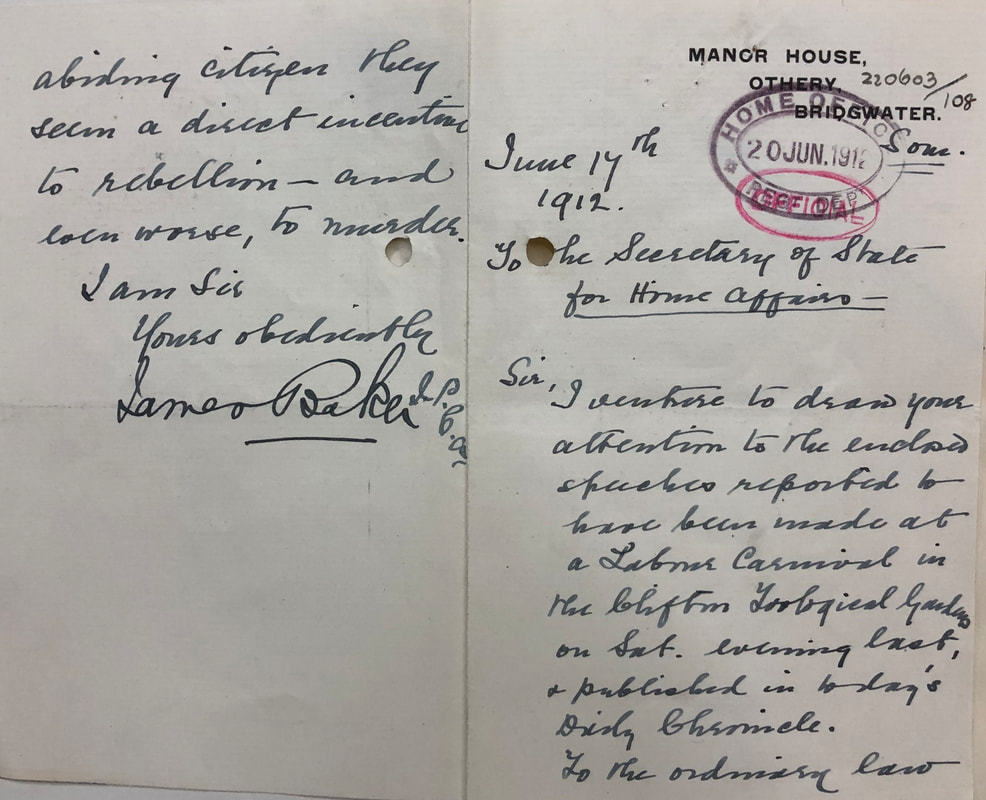

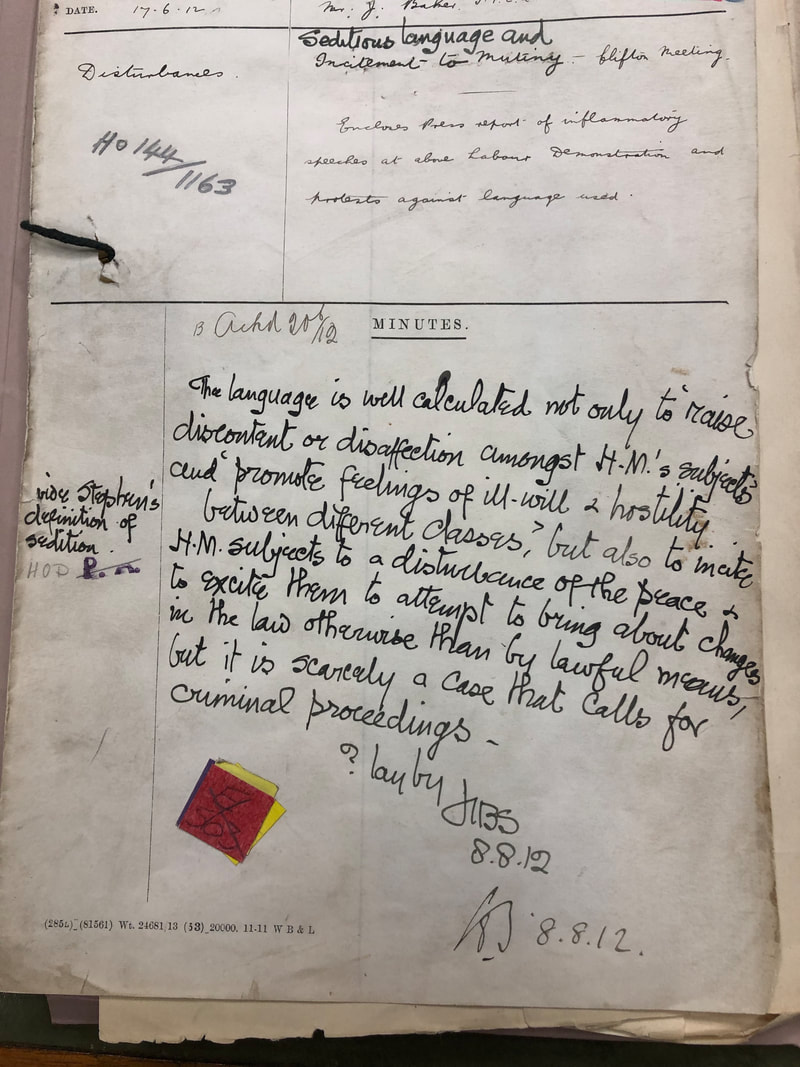

The years running up to the First World War were marked with many industrial disputes as workers joined trade unions in huge numbers to challenge falling real wages and working conditions. Keir Hardie was unsurprisingly to be found supporting workers in struggle across the UK. The government decided on a number of occasions to deploy troops in support of the police. This was attacked by trade unions as an abuse of state power in support of the bosses and speakers at union rallies often called upon working class soldiers to disobey orders. In the National Archives I found a 1912 Home Office file full of complaints from 'concerned citizens' about this, asking why the authorities are not charging the trade union leaders with sedition or similar offences. One such complaint covered a meeting in Bristol at which Keir Hardie spoke. He said: "I only know of two classes of people who can command police and military escort - one the blackleg and the other the Royal family. So far as I can make out, in the eyes of the powers that be, the one is regarded as important as the other. And I dare say that if the capitalist class were called upon to decide whether they would abolish the Royal family or the blackleg they would decide for the latter without hesitation." Another speaker said: "It is not the function of the soldier, maybe your son or brother, to be called out to shoot those who are simply fighting for right and a bit more bread and cheese." One concerned citizen residing at, The Manor House, Othery, Bridgewater, enclosed a copy of the newspaper article in his complaint to the Home Secretary. The letter is on file and is reproduced below. The civil servant who considered the matter was clearly outraged by the speeches. "The language is well calculated, not only to cause discontent and disaffection amongst H.M. subjects and promote feelings of ill will and hostility between different classes." I somehow doubt Keir Hardie would have disagreed with that! Sadly for 'outraged of Bridgewater', the civil servant had to conclude that it wasn't a case that called for criminal proceedings. Pity really, I am sure Keir Hardie would have enjoyed defending himself at that trial. Dave Watson

9 August 2019 |

AuthorThis is the Blog of the Keir Hardie Society. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed